Security experts call it a “drive-by download”: a hacker infiltrates a high-traffic website and then subverts it to deliver malware to every single visitor. It’s one of the most powerful tools in the black hat arsenal, capable of delivering thousands of fresh victims into a hackers’ clutches within minutes.

Now the technique is being adopted by a different kind of a hacker—the kind with a badge. For the last two years, the FBI has been quietly experimenting with drive-by hacks as a solution to one of law enforcement’s knottiest Internet problems: how to identify and prosecute users of criminal websites hiding behind the powerful Tor anonymity system.

The approach has borne fruit—over a dozen alleged users of Tor-based child porn sites are now headed for trial as a result. But it’s also engendering controversy, with charges that the Justice Department has glossed over the bulk-hacking technique when describing it to judges, while concealing its use from defendants. Critics also worry about mission creep, the weakening of a technology relied on by human rights workers and activists, and the potential for innocent parties to wind up infected with government malware because they visited the wrong website. “This is such a big leap, there should have been congressional hearings about this,” says ACLU technologist Chris Soghoian, an expert on law enforcement’s use of hacking tools. “If Congress decides this is a technique that’s perfectly appropriate, maybe that’s OK. But let’s have an informed debate about it.”

The FBI’s use of malware is not new. The bureau calls the method an NIT, for “network investigative technique,” and the FBI has been using it since at least 2002 in cases ranging from computer hacking to bomb threats, child porn to extortion. Depending on the deployment, an NIT can be a bulky full-featured backdoor program that gives the government access to your files, location, web history and webcam for a month at a time, or a slim, fleeting wisp of code that sends the FBI your computer’s name and address, and then evaporates.

What’s changed is the way the FBI uses its malware capability, deploying it as a driftnet instead of a fishing line. And the shift is a direct response to Tor, the powerful anonymity system endorsed by Edward Snowden and the State Department alike.

Tor is free, open-source software that lets you surf the web anonymously. It achieves that by accepting connections from the public Internet—the “clearnet”—encrypting the traffic and bouncing it through a winding series of computers before dumping it back on the web through any of over 1,100 “exit nodes.”

The system also supports so-called hidden services—special websites, with addresses ending in .onion, whose physical locations are theoretically untraceable. Reachable only over the Tor network, hidden services are used by organizations that want to evade surveillance or protect users’ privacy to an extraordinary degree. Some users of such service have legitimate and even noble purposes—including human rights groups and journalists. But hidden services are also a mainstay of the nefarious activities carried out on the so-called Dark Net: the home of drug markets, child porn, murder for hire, and a site that does nothing but stream pirated My Little Pony episodes.

Law enforcement and intelligence agencies have a love-hate relationship with Tor. They use it themselves, but when their targets hide behind the system, it poses a serious obstacle. Last month, Russia’s government offered a $111,000 bounty for a method to crack Tor.

The FBI debuted its own solution in 2012, in an investigation dubbed “Operation Torpedo,” whose contours are only now becoming visible through court filings.

Operation Torpedo began with an investigation in the Netherlands in August 2011. Agents at the National High Tech Crime Unit of the Netherlands’ national police force had decided to crack down on online child porn, according to an FBI affidavit. To that end, they wrote a web crawler that scoured the Dark Net, collecting all the Tor onion addresses it could find.

The NHTCU agents systematically visited each of the sites and made a list of those dedicated to child pornography. Then, armed with a search warrant from the Court of Rotterdam, the agents set out to determine where the sites were located.

That, in theory, is a daunting task—Tor hidden services mask their locations behind layers of routing. But when the agents got to a site called “Pedoboard,” they discovered that the owner had foolishly left the administrative account open with no password. They logged in and began poking around, eventually finding the server’s real Internet IP address in Bellevue, Nebraska.

They provided the information to the FBI, who traced the IP address to 31-year-old Aaron McGrath. It turned out McGrath was hosting not one, but two child porn sites at the server farm where he worked, and a third one at home.

Instead of going for the easy bust, the FBI spent a solid year surveilling McGrath, while working with Justice Department lawyers on the legal framework for what would become Operation Torpedo. Finally, on November 2012, the feds swooped in on McGrath, seized his servers and spirited them away to an FBI office in Omaha.

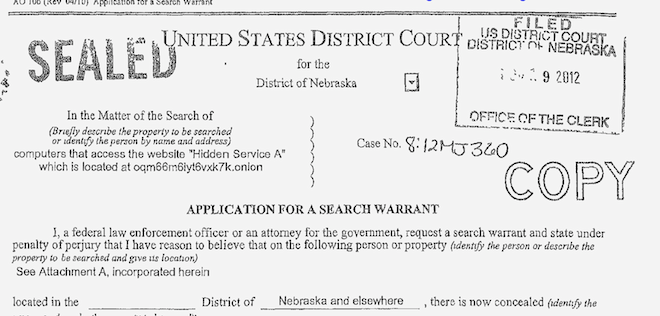

A federal magistrate signed three separate search warrants: one for each of the three hidden services. The warrants authorized the FBI to modify the code on the servers to deliver the NIT to any computers that accessed the sites. The judge also allowed the FBI to delay notification to the targets for 30 days.

This NIT was purpose-built to identify the computer, and do nothing else—it didn’t collect keystrokes or siphon files off to the bureau. And it evidently did its job well. In a two-week period, the FBI collected IP addresses, hardware MAC addresses (a unique hardware identifier for the computer’s network or Wi-Fi card) and Windows hostnames on at least 25 visitors to the sites. Subpoenas to ISPs produced home addresses and subscriber names, and in April 2013, five months after the NIT deployment, the bureau staged coordinated raids around the country.

Today, with 14 of the suspects headed toward trial in Omaha, the FBI is being forced to defend its use of the drive-by download for the first time. Defense attorneys have urged the Nebraska court to throw out the spyware evidence, on the grounds that the bureau concealed its use of the NIT beyond the 30-day blackout period allowed in the search warrant. Some defendants didn’t learn about the hack until a year after the fact. “Normally someone who is subject to a search warrant is told virtually immediately,” says defense lawyer Joseph Gross Jr. “What I think you have here is an egregious violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

But last week U.S. Magistrate Judge Thomas Thalken rejected the defense motion, and any implication that the government acted in bad faith. “The affidavits and warrants were not prepared by some rogue federal agent,” Thalken wrote, “but with the assistance of legal counsel at various levels of the Department of Justice.” The matter will next be considered by U.S. District Judge Joseph Bataillon for a final ruling.

The ACLU’s Soghoian says a child porn sting is probably the best possible use of the FBI’s drive-by download capability. “It’s tough to imagine a legitimate excuse to visit one of those forums: the mere act of looking at child pornography is a crime,” he notes. His primary worry is that Operation Torpedo is the first step to the FBI using the tactic much more broadly, skipping any public debate over the possible unintended consequences. “You could easily imagine them using this same technology on everyone who visits a jihadi forum, for example,” he says. “And there are lots of legitimate reasons for someone to visit a jihadi forum: research, journalism, lawyers defending a case. ACLU attorneys read Inspire Magazine, not because we are particularly interested in the material, but we need to cite stuff in briefs.”

Soghoian is also concerned that the judges who considered NIT applications don’t fully understand that they’re being asked to permit the use of hacking software that takes advantage of software vulnerabilities to breach a machine’s defenses. The Operation Torpedo search warrant application, for example, never uses the words “hack,” “malware,” or “exploit.” Instead, the NIT comes across as something you’d be happy to spend 99 cents for in the App Store. “Under the NIT authorized by this warrant, the website would augment [its] content with some additional computer instructions,” the warrant reads.

From the perspective of experts in computer security and privacy, the NIT is malware, pure and simple. That was demonstrated last August, when, perhaps buoyed by the success of Operation Torpedo, the FBI launched a second deployment of the NIT targeting more Tor hidden services.

This one—still unacknowledged by the bureau—traveled across the servers of Freedom Hosting, an anonymous provider of turnkey Tor hidden service sites that, by some estimates, powered half of the Dark Net.

This attack had its roots in the July 2013 arrest of Freedom Hosting’s alleged operator, one Eric Eoin Marques, in Ireland. Marques faces U.S. charges of facilitating child porn—Freedom Hosting long had a reputation for tolerating child pornography.

Working with French authorities, the FBI got control of Marques’ servers at a hosting company in France, according to testimony in Marques’ case. Then the bureau appears to have relocated them—or cloned them—in Maryland, where the Marques investigation was centered.

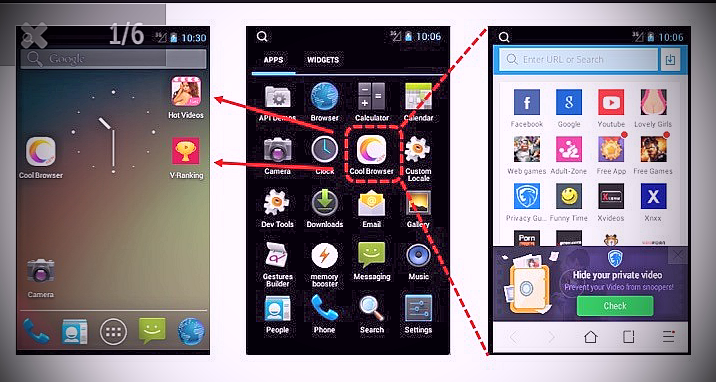

On August 1, 2013, some savvy Tor users began noticing that the Freedom Hosting sites were serving a hidden “iframe”—a kind of website within a website. The iframe contained Javascript code that used a Firefox vulnerability to execute instructions on the victim’s computer. The code specifically targeted the version of Firefox used in the Tor Browser Bundle—the easiest way to use Tor.

This was the first Tor browser exploit found in the wild, and it was an alarming development to the Tor community. When security researchers analyzed the code, they found a tiny Windows program hidden in a variable named “Magneto.” The code gathered the target’s MAC address and the Windows hostname, and then sent it to a server in Virginia in a way that exposed the user’s real IP address. In short, the program nullified the anonymity that the Tor browser was designed to enable.

As they dug further, researchers discovered that the security hole the program exploited was already a known vulnerability called CVE-2013-1690—one that had theoretically been patched in Firefox and Tor updates about a month earlier. But there was a problem: Because the Tor browser bundle has no auto-update mechanism, only users who had manually installed the patched version were safe from the attack. “It was really impressive how quickly they took this vulnerability in Firefox and extrapolated it to the Tor browser and planted it on a hidden service,” says Andrew Lewman, executive director of the nonprofit Tor Project, which maintains the code.

The Freedom Hosting drive-by has had a lasting impact on the Tor Project, which is now working to engineer a safe, private way for Tor users to automatically install the latest security patches as soon as they’re available—a move that would make life more difficult for anyone working to subvert the anonymity system, with or without a court order.

Unlike with Operation Torpedo, the details of the Freedom Hosting drive-by operation remain a mystery a year later, and the FBI has repeatedly declined to comment on the attack, including when contacted by WIRED for this story. Only one arrest can be clearly tied to the incident—that of a Vermont man named Grant Klein who, according to court records, was raided in November based on an NIT on a child porn site that was installed on July 31, 2013. Klein pleaded guilty to a single count of possession of child pornography in May and is set for sentencing this October.

But according to reports at the time, the malware was seen, not just on criminal sites, but on legitimate hidden services that happened to be hosted by Freedom Hosting, including the privacy protecting webmail service Tormail. If true, the FBI’s drive-by strategy is already gathering data on innocent victims.

Despite the unanswered questions, it’s clear that the Justice Department wants to scale up its use of the drive-by download. It’s now asking the Judicial Conference of the United States to tweak the rules governing when and how federal judges issue search warrants. The revision would explicitly allow for warrants to “use remote access to search electronic storage media and to seize or copy electronically stored information” regardless of jurisdiction.

The revision, a conference committee concluded last May (.pdf), is the only way to confront the use of anonymization software like Tor, “because the target of the search has deliberately disguised the location of the media or information to be searched.”

Such dragnet searching needs more scrutiny, Soghoian says. “What needs to happen is a public debate about the use of this technology, and the use of these techniques,” he says. “And whether the criminal statutes that the government relies on even permit this kind of searching. It’s one thing to say we’re going to search a particular computer. It’s another thing to say we’re going to search every computer that visits this website, without knowing how many there are going to be, without knowing what city, state or countries they’re coming from.”

“Unfortunately,” he says, “we’ve tiptoed into this area, because the government never gave notice that they were going to start using this technique.”

For more information follow the source link below.

Source: Wired